Anteater

| Anteaters Temporal range: Early Miocene – present,

| |

|---|---|

| |

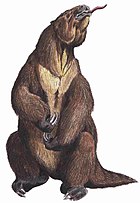

| Giant anteater | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Pilosa |

| Suborder: | Vermilingua Illiger, 1811 |

| Families | |

| |

| Red: Cyclopedidae, Blue: Myrmecophagidae, Purple: both Cyclopedidae and Myrmecophagidae | |

Anteaters are the four extant mammal species in the suborder Vermilingua[1] (meaning "worm tongue"), commonly known for eating ants and termites. The individual species have other names in English and other languages. Together with sloths, they are within the order Pilosa.

Extant species are the giant anteater Myrmecophaga tridactyla, about 1.8 m (5 ft 11 in) long including the tail; the silky anteater Cyclopes didactylus, about 35 cm (14 in) long; the southern tamandua or collared anteater Tamandua tetradactyla, about 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in) long; and the northern tamandua Tamandua mexicana of similar dimensions.

Etymology

The name anteater refers to the species' diet, which consists mainly of ants and termites. Anteater has also been used as a common name for a number of animals that are not in Vermilingua, including the echidnas, numbat, pangolins, and aardvark.[2][3] Anteaters are also known as antbears, although this is more commonly used as a name for the aardvark.[4] The word tamandua comes from Portuguese, which itself borrowed it from the Tupí tamanduá, meaning "ant hunter".[5] In Portuguese, tamanduá is used to refer to all anteaters; in Spanish, only the two species in the genus Tamandua are known by this name, with the giant anteater and silky anteater being called oso hormiguero and cíclope, respectively. All four species are also known by a number of indigenous names.[6]

Taxonomy

Evolutionary history

Anteaters are part of the Xenarthra superorder, a once diverse group of mammals that occupied South America while it was geographically isolated from the invasion of animals from North America, with the other two remaining animals in the family being the sloths and the armadillos.

At one time, anteaters were assumed to be related to aardvarks and pangolins because of their physical similarities to those animals, but these similarities have since been determined to be not a sign of a common ancestor, but of convergent evolution. All have evolved powerful digging forearms, long tongues, and toothless, tube-like snouts to subsist by raiding termite mounds.

Taxonomy

The anteaters are more closely related to the sloths than they are to any other group of mammals. Their next closest relations are armadillos. There are four extant species in three genera. There are several extinct genera as well.

Suborder Vermilingua (anteaters)

- Family Cyclopedidae

- Genus Cyclopes

- Silky anteater (C. didactylus)

- Genus †Palaeomyrmidon (Rovereto 1914)[9]

- Genus Cyclopes

- Family Myrmecophagidae

- Genus Myrmecophaga

- Giant anteater (M. tridactyla)

- Genus †Neotamandua (Rovereto 1914)[10]

- Genus Tamandua

- Northern tamandua (T. mexicana)

- Southern tamandua (T. tetradactyla)

- Genus †Protamandua (Ameghino 1904)[11]

- Genus Myrmecophaga

Morphology

All anteaters have extremely elongated snouts equipped with a thin and long tongue that is coated with sticky saliva produced by enlarged submaxillary glands. The mouth is small and has no teeth. The frontal feet have large claws on the third digit, used to break into the mounds of termites and ants, and the remaining digits are usually slightly smaller or lacking entirely. The entire body is covered with dense fur. The tail is long, in some cases as long as the rest of the body, covered with varying amounts of fur, and prehensile in all species except for the giant anteater.[12][13] Anteaters are known to experience color abnormalities, including albinism in giant anteaters and albinism, leucism, and melanism in the southern tamandua.[14]

The giant anteater can be distinguished from the other species on the basis of its large size, with an average total body length of around 2 m (6.6 ft) and an average mass of 33 kg (73 lb). The body is mainly covered with long, dark brown or black fur, with a prominent triangular white-edged black band from the shoulders down to chest and continuing to the mid-body. The forelegs are mostly white, marked with black at the wrists and just above the claws. The tail is almost as long as the body and covered with long, coarse hairs.[12][13][15] Giant anteaters have the largest degree of rostral elongation relative to their size of any other ant-eating mammal.[16]

The tamanduas are medium-sized species smaller than the giant anteater, with a total body length of around 0.77–1.33 m (2.5–4.4 ft) and a mass of 3.2–7.0 kg (7.1–15.4 lb). They can further be distinguished by their shorter snout, their relatively shorter claws, proportionately longer ears, and mostly fur-less, prehensile tail. They also differ in their coloration; most individuals are golden brown to gray, with a black "vest" on the back and belly joined by two black bands running across the shoulders. Some tamanduas may lack the vest partially or entirely, instead having a uniformly yellow, brown, or black coat.[12][13]

The silky anteater is the smallest species in the order, with an average total body length of 43 cm (17 in) and an average mass of 235 g (8.3 oz).[13] It has extremely dense, silky, gray to golden-brown fur across its body, sometimes tinged silver on the back.[12][17] Some South American populations have a chocolate brown stripe down the middle of the back, most prominent in the Amazon basin.[17] The tail is extremely prehensile, and the limbs display adaptations to help it grab items while climbing.[13] Unlike the other anteaters and many other unrelated obligate ant-eating mammals,[18] the silky anteater's face is only slightly longer than expected for an animal of its size and shows a strong downward tilt.[16]

Distribution and habitat

Anteaters are endemic to the New World, where they are found on the mainland from southern Mexico to northern Argentina,[12] as well as some of the Caribbean islands.[17][19] Like other xenarthans, anteaters originally evolved in South America,[20] and began spreading to Central and North America as part of the Great American Interchange after the formation of the Isthmus of Panama around 3 million years ago.[21] Some species of anteaters may have had greater ranges during the early Pleistocene than they have currently; for example, fossils of the giant anteater have been found as far north as Sonora, Mexico, and the reduction in its range is probably due to changes in habitat due to deglaciation in North America in the later Pleistocene.[22]

Currently, the giant anteater is known from Central America south east of the Andes to northern Argentina, Bolivia, and Paraguay. West of the Andes, it is only known from Colombia and possibly Ecuador. It has been extirpated from much of its Central American range, and has also suffered local extinctions in the southern end of its distribution.[15] The northern tamandua is found from southern Mexico south to the western Andes of Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, and Ecuador,[23] while the southern tamandua inhabits South America east of the Andes, from as far north as Colombia, Trinidad, and the Guianas south to northern Uruguay and northern Argentina.[19] Both species of tamandua co-occur in some parts of their range.[23] The silky anteater occurs from Veracruz and Oaxaca in Mexico south to Colombia and Ecuador west of the Andes and to Brazil and Bolivia east of the Andes. An additional disjunct population also exists in northwestern Brazil.[17]

Anteater habitats include dry tropical forests, rainforests, grasslands, and savannas. The silky anteater is specialized to an arboreal environment, but the more opportunistic tamanduas find their food both on the ground and in trees, typically in dry forests near streams and lakes. The almost entirely terrestrial giant anteater lives in savannas.[24] The two anteaters of the genus Tamandua, the southern and the northern tamanduas are much smaller than the giant anteater, and differ essentially from it in their habits, being mainly arboreal. They inhabit the dense primeval forests of South and Central America.[25] The silky anteater (Cyclopes didactylus) is a native of the hottest parts of South and Central America and exclusively arboreal in its habits.[25]

Behavior and ecology

Anteaters are mostly solitary mammals prepared to defend their 1.0 to 1.5 sq mi (2.6 to 3.9 km2) territories. They do not normally enter a territory of another anteater of the same sex, but males often enter the territory of associated females. When a territorial dispute occurs, they vocalize, swat, and can sometimes sit on or even ride the back of their opponents.[24]

Anteaters have poor sight but an excellent sense of smell, and most species depend on the latter for foraging, feeding, and defence. Their hearing is thought to be good.[24]

With a body temperature fluctuating between 33 and 36 °C (91 and 97 °F), anteaters, like other xenarthrans, have among the lowest body temperatures of any mammal,[26] and can tolerate greater fluctuations in body temperature than most mammals. Their daily energy intake from food is only slightly greater than their energy need for daily activities, and anteaters probably coordinate their body temperatures so they keep cool during periods of rest, and heat up during foraging.[24]

Reproduction

Adult males are slightly larger and more muscular than females, and have wider heads and necks. Visual sex determination can, however, be difficult, since the penis and testes are located internally between the rectum and urinary bladder in males and females have a single pair of mammae near the armpits. Fertilization occurs by contact transfer without intromission, similar to some lizards. Polygynous mating usually results in a single offspring; twins are possible but rare. The large foreclaws prevent mothers from grasping their newborns and they therefore have to carry the offspring until they are self-sufficient.[24]

Foraging and diet

Anteaters are specialized to feed on small insects, with each anteater species having its own insect preferences: small species are specialized on arboreal insects living on small branches, while large species can penetrate the hard covering of the nests of terrestrial insects. To avoid the jaws, sting, and other defences of the invertebrates, anteaters have adopted the feeding strategy of licking up large numbers of ants and termites as quickly as possible – an anteater normally spends about a minute at a nest before moving on to another – and a giant anteater has to visit up to 200 nests per day to consume the thousands of insects it needs to satisfy its caloric requirements.[24]

The anteater's tongue is covered with thousands of tiny hooks called filiform papillae which are used to hold the insects together with large amounts of saliva. Swallowing and the movement of the tongue are aided by side-to-side movements of the jaws. The tongue is attached to the sternum and moves very quickly, flicking 150 times per minute. The anteater's stomach, similar to a bird's gizzard, has hardened folds and uses strong contractions to grind the insects, a digestive process assisted by small amounts of ingested sand and dirt.[24]

Predators

A number of mammals and birds are known to prey on anteaters. Jaguars are known to feed upon both giant anteaters and the southern tamandua, with the latter species representing a significant portion of the jaguar's diet in some areas.[27][28] Tamanduas are additionally predated upon by ocelots, other felids, foxes,[12] and caimans,[29] and may be vulnerable to predation by harpy eagles near their nests.[30] Silky anteaters have been observed being attacked by hawks.[31]

Diseases and parasites

Anteaters are known to host a wide variety of parasites, including ticks, fleas, parasitic worms, and acanthocephalans.[32] The most common ticks found on anteaters are from the family Ixodidae, and especially the genus Amblyomma: 29 species of ixodids are known from anteaters, 25 of which belong to Amblyomma.[33] Anteaters are the primary host for at least four species of ticks: A. nodosum, A. calcaratum, A. goeldi, and A. pictum.[34] Parasitic worms collected from anteaters include those in the class Cestoda and nematodes in the families Spiruridae, Physalopteridae, Trichostrongylidae, and Ascarididae.[35][36] Parasitization by the nematode Physaloptera magnipapilla results in anemia and gastritis in the giant anteater.[37] The giant anteater is the type host of a species of nematode, Aspidodera serrata,[38] while the silky anteater is the type host of the coccidian Eimeria cyclopei.[39] Other parasites that affect anteaters are protozoans, bacteria, parabasalids, and viruses.[36][40]

Diseases that anteaters suffer from include physiological diseases like Sertoli cell tumors,[35][41] physical injuries such as burns and fractures, metabolic and nutritional disorders like soft tissue mineralization and hypervitaminosis D,[36][42] and infectious diseases like gastritis,[citation needed] osteomyelitis,[43] and dermatitis.[36] Anteaters may serve as vectors for the transmission of several diseases between species.[33][44] Ticks from anteaters are known to carry Rickettsia bacteria, which cause spotted fever in humans.[33][45] Anteaters have also been infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19,[44] Leishmania, the protozoan that causes leishmaniasis,[46] and canine distemper-causing Morbillivirus, contracting the last disease from a maned wolf in captivity.[47][48] Anteaters, like other xenarthans, display several adaptations that lead to very low rates of cancer among them, such as programmed cell death at very low levels of DNA damage.[49]

Conservation

The silky anteater and both of the tamanduas are classified as being of least concern by the IUCN due to their large ranges, presumed large populations, and the lack of significant enough population declines.[50][51][52] The giant anteater is classified as being vulnerable due to high levels of habitat loss and degradation, an ongoing population decline of greater than 30% in the last 21 years, and a number of threats such as hunting and wildfires.[53] Additionally, the population of the silky anteater from northeastern Brazil has been assessed separately by the IUCN and classified as being data deficient, although its population is currently thought to be decreasing due habitat loss and illegal capture for the wildlife trade.[54]

References

- ^ "Giant Anteater Facts". Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 2011-08-28. Retrieved 2011-07-30.

- ^ "Anteater". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OED/1002244695. Retrieved 19 August 2023. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "Definition of ANTEATER". www.merriam-webster.com. 2023-07-11. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ "Ant bear". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OED/4378206907. Retrieved 20 August 2023. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "Tamandua". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OED/1093689655. Retrieved 19 August 2023. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Superina, Mariella; Aguiar, John M. (2006). "A Reference List of Common Names for the Edentates". Edentata. 7 (1): 33. doi:10.1896/1413-4411.7.1.33. S2CID 84399406.

- ^ Presslee, Samantha; Slater, Graham J.; Pujos, François; Forasiepi, Analía M.; Fischer, Roman; Molloy, Kelly; Mackie, Meaghan; Olsen, Jesper V.; Kramarz, Alejandro; Taglioretti, Matías; Scaglia, Fernando; Lezcano, Maximiliano; Lanata, José Luis; Southon, John; Feranec, Robert; Bloch, Jonathan; Hajduk, Adam; Martin, Fabiana M.; Salas Gismondi, Rodolfo; Reguero, Marcelo; de Muizon, Christian; Greenwood, Alex; Chait, Brian T.; Penkman, Kirsty; Collins, Matthew; MacPhee, Ross D. E. (6 June 2019). "Palaeoproteomics resolves sloth relationships" (PDF). Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (7): 1121–1130. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0909-z. PMID 31171860. S2CID 174813630.

- ^ Gibb, G. C.; Condamine, F. L.; Kuch, M.; Enk, J.; Moraes-Barros, N.; Superina, M.; Poinar, H. N.; Delsuc, F. (2015). "Shotgun Mitogenomics Provides a Reference PhyloGenetic Framework and Timescale for Living Xenarthrans". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 33 (3): 621–642. doi:10.1093/molbev/msv250. PMC 4760074. PMID 26556496.

- ^ Palaeomyrmidon in the Paleobiology Database

- ^ Neotamandua in the Paleobiology Database

- ^ Protamandua in the Paleobiology Database

- ^ a b c d e f Eisenberg, John Frederick; Redford, Kent H. (1999). Mammals of the Neotropics. 3: The Central neotropics: Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 90–94. ISBN 978-0-226-19542-1.

- ^ a b c d e Gardner, Alfred L. (2007). Mammals of South America. Chicago: University of Chicago press. pp. 168–177. ISBN 978-0-226-28240-4.

- ^ Bôlla, Daniela; Baraldo-Mello, João P.; Garcia, Thierry; Rovito, Sean (2022). "Color abnormalities in the Giant Anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla Linnaeus, 1758) and Southern Tamandua (Tamandua tetradactyla [Linnaeus, 1758]) from Brazil and Ecuador". Notas sobre Mamíferos Sudamericanos (in Spanish). 04 (1): 001–008. doi:10.31687/SaremNMS22.11.2. ISSN 2618-4788.

- ^ a b Gaudin, Timothy J; Hicks, Patrick; Di Blanco, Yamil (12 April 2018). "Myrmecophaga tridactyla (Pilosa: Myrmecophagidae)". Mammalian Species. 50 (956): 1–13. doi:10.1093/mspecies/sey001. hdl:11336/90534.

- ^ a b Naples, Virginia L. (September 1999). "Morphology, evolution and function of feeding in the giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla)". Journal of Zoology. 249 (1): 19–41. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1999.tb01057.x. ISSN 0952-8369.

- ^ a b c d Hayssen, Virginia; Miranda, Flávia; Pasch, Bret (25 January 2012). "Cyclopes didactylus (Pilosa: Cyclopedidae)". Mammalian Species. 44: 51–58. doi:10.1644/895.1. S2CID 86110792.

- ^ REISS, KAREN ZICH (2000). "Feeding in Myrmecophagous Mammals". In Schwenk, Kurt (ed.). Feeding. Elsevier. pp. 459–485. doi:10.1016/b978-012632590-4/50016-2. ISBN 978-012632590-4.

- ^ a b Hayssen, Virginia (21 January 2011). "Tamandua tetradactyla (Pilosa: Myrmecophagidae)". Mammalian Species. 43: 64–74. doi:10.1644/875.1. S2CID 86324706.

- ^ McDonald, H. Gregory; Naples, Virginia L. (2008). "Xenarthra". Evolution of Tertiary Mammals of North America. pp. 147–160. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511541438.011. ISBN 978-0-521-78117-6.

- ^ Shaw, Barbara J (2010). The enigmatic anteaters, sloths, and armadillos: Elucidating evolutionary relationships among xenarthran families, †Ernanodon antelios, and remaining mammals (Thesis). ProQuest 839582487.[page needed]

- ^ Desbiez, A. L. G.; Chiarello, A. G.; Teles, Davi (2020). Alberici, V. (ed.). Survival Blueprint for the conservation of the giant anteater, Myrmecophaga tridactyla, in the Brazilian Cerrado (PDF). London: Zoological Society of London.

- ^ a b Navarrete, Daya; Ortega, Jorge (28 March 2011). "Tamandua mexicana (Pilosa: Myrmecophagidae)". Mammalian Species. 43 (874): 56–63. doi:10.1644/874.1. S2CID 31010025.

- ^ a b c d e f g Grzimek, Bernhard (2004). Hutchins, Michael; Kleiman, Devra G; Geist, Valerius; McDade, Melissa С (eds.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Vol. 13 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Gale. pp. 171–175. ISBN 978-0-7876-7750-3.

- ^ a b One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Anteater". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 89.

- ^ Lovegrove, B. G. (August 2000). "The Zoogeography of Mammalian Basal Metabolic Rate". The American Naturalist. 156 (2). The University of Chicago Press: 201–219, see 214–215. doi:10.1086/303383. JSTOR 3079219. PMID 10856202. S2CID 4436119.

- ^ Foster, Vania C.; Sarmento, Pedro; Sollmann, Rahel; Tôrres, Natalia; Jácomo, Anah T. A.; Negrões, Nuno; Fonseca, Carlos; Silveira, Leandro (2013). "Jaguar and Puma Activity Patterns and Predator-Prey Interactions in Four Brazilian Biomes". Biotropica. 45 (3): 378. Bibcode:2013Biotr..45..373F. doi:10.1111/btp.12021. S2CID 86338173.

- ^ Cavalcanti, Sandra M. C.; Gese, Eric M. (2010-06-16). "Kill rates and predation patterns of jaguars ( Panthera onca ) in the southern Pantanal, Brazil". Journal of Mammalogy. 91 (3): 722–736. doi:10.1644/09-MAMM-A-171.1. ISSN 0022-2372.

- ^ Vasconcelos, Beatriz Diogo; Brandao, Reuber (2022). "Predation on Tamandua tetradactyla (Pilosa: Myrmecophagidae) by Caiman latirostris (Crocodylia: Alligatoridae) in a highly seasonal habitat in Central Brazil" (PDF). North-Western Journal of Zoology. 18 (2): 218.

- ^ Aguiar-Silva, Francisca Helena; Jaudoin, Olivier; Sanaiotti, Tânia M.; Seixas, Gláucia H.F.; Duleba, Samuel; Martins, Frederico D. (2017). "Camera Trapping at Harpy Eagle Nests: Interspecies Interactions Under Predation Risk". Journal of Raptor Research. 51 (1): 72–78. doi:10.3356/JRR-15-58.1. ISSN 0892-1016. S2CID 90034136.

- ^ Barnett, Adrian A.; Silla, João M.; de Oliveira, Tadeu; Boyle, Sarah A.; Bezerra, Bruna M.; Spironello, Wilson R.; Setz, Eleonore Z. F.; da Silva, Rafaela F. Soares; de Albuquerque Teixeira, Samara; Todd, Lucy M.; Pinto, Liliam P. (2017). "Run, hide, or fight: anti-predation strategies in endangered red-nosed cuxiú (Chiropotes albinasus, Pitheciidae) in southeastern Amazonia". Primates. 58 (2): 353–360. doi:10.1007/s10329-017-0596-9. ISSN 0032-8332. PMID 28116549. S2CID 254159850.

- ^ Sanchez, Juliana P.; Berrizbeitia, M. Fernanda López; Ezquiaga, M. Cecilia (September 2023). "Host specificity of flea parasites of mammals from the Andean Biogeographic Region". Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 37 (3): 511–522. doi:10.1111/mve.12649. PMID 37000587. S2CID 257856374.

- ^ a b c Muñoz-García, Claudia Irais; Guzmán-Cornejo, Carmen; Rendón-Franco, Emilio; Villanueva-García, Claudia; Sánchez-Montes, Sokani; Acosta-Gutierrez, Roxana; Romero-Callejas, Evangelina; Díaz-López, Hilda; Martínez-Carrasco, Carlos; Berriatua, Eduardo (August 2019). "Epidemiological study of ticks collected from the northern tamandua (Tamandua mexicana) and a literature review of ticks of Myrmecophagidae anteaters". Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases. 10 (5): 1146–1156. doi:10.1016/j.ttbdis.2019.06.005. PMID 31231044. S2CID 195327955.

- ^ Kolonin, G. V. (July 2007). "Mammals as hosts of Ixodid ticks (Acarina, Ixodidae)". Entomological Review. 87 (4): 401–412. doi:10.1134/S0013873807040033. S2CID 23409847.

- ^ a b Diniz, L. S. M.; Costa, E. O.; Oliveira, P. M. A. (September 1995). "Clinical disorders observed in anteaters (Myrmecophagidae, Edentata) in captivity". Veterinary Research Communications. 19 (5): 409–415. doi:10.1007/BF01839320. PMID 8560755. S2CID 30645943.

- ^ a b c d Arenales, Alexandre; Gardiner, Chris H; Miranda, Flavia R; Dutra, Kateanne S; Oliveira, Ayisa R; Mol, Juliana PS; Texeira da Costa, Maria EL; Tinoco, Herlandes P; Coelho, Carlyle M; Silva, Rodrigo OS; Pinto, Hudson A; Hoppe, Estevam GL; Werther, Karin; Santos, Renato Lima (October 2020). "Pathology of Free-Ranging and Captive Brazilian Anteaters". Journal of Comparative Pathology. 180: 55–68. doi:10.1016/j.jcpa.2020.08.007. PMID 33222875. S2CID 224857889.

- ^ Lértora, Walter Javier; Montenegro, M. A.; Mussart, Norma Beatriz; Villordo, Gabriela Inés; Sánchez Negrette, Marcial (February 2015). "Anemia and hyperplastic gastritis in a giant anteater (myrmecophaga tridactyla) due to physaloptera magnipapilla parasitism". Brazilian Journal of Veterinary Pathology. 9 (1): 20–26. hdl:123456789/28376.

- ^ Cesário, Clarice S.; Gomes, Ana Paula N.; Maldonado, Arnaldo; Olifiers, Natalie; Jiménez, Francisco A.; Bianchi, Rita C. (10 February 2021). "A New Species of Aspidodera (Nematoda: Heterakoidea) Parasitizing the Giant Anteater Myrmecophaga tridactyla (Pilosa: Myrmecophagidae) in Brazil and New Key to Species". Comparative Parasitology. 88 (1). doi:10.1654/1525-2647-88.1.7. S2CID 233914359.

- ^ Lainson, Ralph; Shaw, Jeffrey J. (1982). "Coccidia of Brazilian edentates: Eimeria cyclopei n.sp. from the silky anteater, Cyclopes didactylus (Linn.) and Eimeria choloepi n.sp. from the two-toed sloth, Choloepus didactylus (Linn.)". Systematic Parasitology. 4 (3): 269–278. doi:10.1007/BF00009629. ISSN 0165-5752. S2CID 25858346.

- ^ Ibañez-Escribano, A.; Nogal-Ruiz, J.J.; Delclaux, M.; Martinez-Nevado, E.; Ponce-Gordo, F. (August 2013). "Morphological and molecular identification of Tetratrichomonas flagellates from the giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla)". Research in Veterinary Science. 95 (1): 176–181. doi:10.1016/j.rvsc.2013.01.022. PMID 23465778.

- ^ Santana, Clarissa H.; Souza, Lucas dos R. de; Silva, Laice A. da; Oliveira, Ayisa R.; Paula, Nayara F. de; Santos, Daniel O. dos; Pereira, Fernanda M.A.M.; Vieira, André D.; Ribeiro, Letícia N.; Soares-Neto, Lauro L.; Bicudo, Alexandre L. da Costa; Hippolito, Alícia G.; Paixão, Tatiane A. da; Santos, Renato L. (July 2023). "Metastatic Sertoli cell tumour in a captive giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla)". Journal of Comparative Pathology. 204: 17–22. doi:10.1016/j.jcpa.2023.05.001. PMID 37321133. S2CID 259176224.

- ^ Cole, Georgina C.; Naylor, Adam D.; Hurst, Emma; Girling, Simon J.; Mellanby, Richard J. (17 March 2020). "Hypervitaminosis D in a Giant Anteater (Myrmecophaga Tridactyla) and a Large Hairy Armadillo (Chaetophractus Villosus) Receiving a Commercial Insectivore Diet". Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 51 (1): 245–248. doi:10.1638/2019-0042. PMID 32212572. S2CID 213184615.

- ^ Cotts, Leonardo; Amaral, Roberta V.; Laeta, Maíra; Cunha-Filho, Carlos A.; Moratelli, Ricardo (December 2019). "Pathology in the appendicular bones of southern tamandua, Tamandua tetradactyla (Xenarthra, Pilosa): injuries to the locomotor system and first case report of osteomyelitis in anteaters". BMC Veterinary Research. 15 (1): 120. doi:10.1186/s12917-019-1869-x. PMC 6485120. PMID 31023313.

- ^ a b Pereira, Asheley Henrique Barbosa; Pereira, Gabriela Oliveira; Borges, Jaqueline Camargo; de Barros Silva, Victoria Luiza; Pereira, Bárbara Hawanna Marques; Morgado, Thays Oliveira; da Silva Cavasani, Joao Paulo; Slhessarenko, Renata Dezengrini; Campos, Richard Pacheco; Biondo, Alexander Welker; de Carvalho Mendes, Renan; Néspoli, Pedro Eduardo Brandini; de Souza, Marcos Almeida; Colodel, Edson Moleta; Ubiali, Daniel Guimarães; Dutra, Valéria; Nakazato, Luciano (December 2022). "A Novel Host of an Emerging Disease: SARS-CoV-2 Infection in a Giant Anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla) Kept Under Clinical Care in Brazil". EcoHealth. 19 (4): 458–462. doi:10.1007/s10393-022-01623-6. PMC 9872066. PMID 36692797.

- ^ Szabó, Matias Pablo Juan; Pascoal, Jamile Oliveira; Martins, Maria Marlene; Ramos, Vanessa do Nascimento; Osava, Carolina Fonseca; Santos, André Luis Quagliatto; Yokosawa, Jonny; Rezende, Lais Miguel; Tolesano-Pascoli, Graziela Virginia; Torga, Khelma; de Castro, Márcio Botelho; Suzin, Adriane; Barbieri, Amália Regina Mar; Werther, Karin; Silva, Juliana Macedo Magnino; Labruna, Marcelo Bahia (April 2019). "Ticks and Rickettsia on anteaters from Southeast and Central-West Brazil". Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases. 10 (3): 540–545. doi:10.1016/j.ttbdis.2019.01.008. PMID 30709660. S2CID 73441483.

- ^ Muñoz-García, Claudia I.; Sánchez-Montes, Sokani; Villanueva-García, Claudia; Romero-Callejas, Evangelina; Díaz-López, Hilda M.; Gordillo-Chávez, Elías J.; Martínez-Carrasco, Carlos; Berriatua, Eduardo; Rendón-Franco, Emilio (April 2019). "The role of sloths and anteaters as Leishmania spp. reservoirs: a review and a newly described natural infection of Leishmania mexicana in the northern anteater". Parasitology Research. 118 (4): 1095–1101. doi:10.1007/s00436-019-06253-6. PMID 30770980. S2CID 253977205.

- ^ Debesa Belizário Granjeiro, Melissa; Lima Kavasaki, Mayara; Morgado, Thais O.; Avelino Dandolini Pavelegini, Lucas; Alves de Barros, Marisol; Fontana, Carolina; Assis Bianchini, Mateus; Oliveira Souza, Aneliza; Gonçalves Lima Oliveira Santos, Amanda R.; Lunardi, Michele; Colodel, Edson M.; Aguiar, Daniel M.; Jorge Mendonça, Adriane (August 2020). "First report of a canine morbillivirus infection in a giant anteater ( Myrmecophaga tridactyla ) in Brazil". Veterinary Medicine and Science. 6 (3): 606–611. doi:10.1002/vms3.246. PMC 7397876. PMID 32023667.

- ^ Souza, Lucas R.; Carvalho, Marcelo P. N.; Lopes, Carlos E. B.; Lopes, Marcelo C.; Campos, Bruna H.; Teixeira, Érika P. T.; Mendes, Ellen J.; Santos, Leidilene P.; Caixeta, Eduardo A.; Costa, Erica A.; Cunha, João L. R.; Fraiha, Ana L. S.; Silva, Rodrigo O. S.; Ramos, Carolina P.; Varaschin, Mary S.; Ecco, Roselene (September 2022). "Outbreak of canine distemper and coinfections in a maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus) and in three giant anteaters (Myrmecophaga tridactyla)". Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 53 (3): 1731–1741. doi:10.1007/s42770-022-00783-5. PMC 9433619. PMID 35864379.

- ^ Vazquez, Juan Manuel; Pena, Maria T; Muhammad, Baaqeyah; Kraft, Morgan; Adams, Linda B; Lynch, Vincent J (8 December 2022). "Parallel evolution of reduced cancer risk and tumor suppressor duplications in Xenarthra". eLife. 11. doi:10.7554/eLife.82558. PMC 9810328. PMID 36480266.

- ^ Miranda, F.; Meritt, D.A.; Tirira, D.G.; Arteaga, M. (2014). "Cyclopes didactylus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T6019A47440020. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T6019A47440020.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Ortega Reyes, J.; Tirira, D.G.; Arteaga, M.; Miranda, F. (2014). "Tamandua mexicana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T21349A47442649. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T21349A47442649.en. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Miranda, F.; Fallabrino, A.; Arteaga, M.; Tirira, D.G.; Meritt, D.A.; Superina, M. (2014). "Tamandua tetradactyla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T21350A47442916. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T21350A47442916.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Miranda, F.; Bertassoni, A.; Abba, A. M. (2014). "Myrmecophaga tridactyla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T14224A47441961. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T14224A47441961.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Miranda, F.; Superina, M. (2014). " Cyclopes didactylus (Northeastern Brazil subpopulation)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T173393A47444393. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T173393A47444393.en. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

External links

Media related to Vermilingua at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Vermilingua at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Vermilingua at Wikispecies

Data related to Vermilingua at Wikispecies